08.07.2022 –

30.10.2022

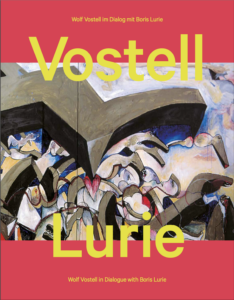

ART AFTER THE SHOAH – Wolf Vostell in dialogue with Boris Lurie

Two artists, one theme – when Wolf Vostell (1932–1998) and Boris Lurie (1924–2008) met in the 1960s, they soon shared more than friendship. Both adopted political positions with their art, both contended with the reappraisal of the inconceivable horrors of the Holocaust, and both opposed war, cruelty and crimes against humanity with every means at their disposal. Their raw works resist the simple consumption that appeared to them as an abomination of the art business. The works of the two artists seem more relevant than ever today, as they rely on a kind of shock therapy, with which the attention of the audience is drawn to the continuity of violence and contempt for humanity.

Wolf Vostell is one of the most important German artists of the 20th century, and is known in particular as a co-founder of the Fluxus movement. On the occasion of his 90th birthday, Kunsthaus Dahlem is dedicating an exhibition to him and his artist colleague Boris Lurie, which will focus on the artistic reappraisal of the Holocaust and the most recent German past.

Wolf Vostell is linked with the exhibition location by a special history: the politically active artist moved from the Rhineland to Berlin at the beginning of the 1970s. The move to the »tragic climatic health resort«, as he called Berlin, appeared to him to be absolutely necessary: »Because [the place] contains our history after all, and I process this history in my paintings and in my objects.« In 1984 the City of Berlin gave Vostell lifetime use of a studio in Dahlem. The new domain was located in a representative studio building that the National Socialists had constructed for Arno Breker from 1938 to 1942. Breker not only enjoyed many privileges as an artist during the National Socialist era, but also implemented the ideology and aesthetic of the regime with his works.

At this historical site, Wolf Vostell continued the contention with the German history of the 20th century he had begun in the late 1950s. Vostell realized the reappraisal of the National Socialist dictatorship and of the Holocaust in all creative phases, with a density and diversity of artistic means like hardly any other artist of his time.

Select works by Boris Lurie enter into a dialogue with Wolf Vostell in the exhibition. The two artists had been close friends since the 1960s. Lurie grew up in Riga and experienced the horrors of the Shoah as a Jew at first hand. Vostell strived to relate to these traumatic experiences as a German. An increasingly intensive exchange developed between the two artists.

Lurie’s art was not aimed at eliciting sympathy for the victims of the Shoah, »but instead at horrifying«. His declared objective was to tear the public out of its complacent passivity and bring home to it the continuation of criminal systems. The two artist friends pursued similar goals and strategies, not only thematically, but also stylistically and formally. The exhibition at Kunsthaus Dahlem traces the many parallels in terms of style and content in detail for the first time.

Curator of the exhibition: Eckhart J. Gillen.

The exhibition catalog (German/English) is edited by Eckhart J. Gillen and Dorothea Schöne.

The exhibition has been funded by the Stiftung Deutsche Klassenlotterie Berlin.