01.11.2022 –

12.02.2023

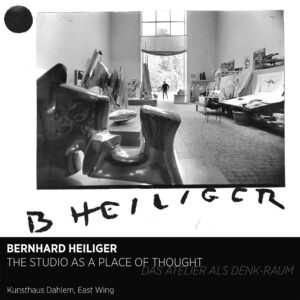

BERNHARD HEILIGER – The studio as a place of thought

Plato (about 427–347 BC) once came to the conclusion that the place in which thought appears sets the direction for its movement. In the 1970s, various philosophers broadened the understanding of place and space, especially public space. Thus, for example, Gilles Deleuze (1925–1995) and Felix Guattari (1930–1992) outlined: different surfaces of social, political, cultural, and other discourses co-exist in constant motion, inter-penetrating each other and crossing physical spaces; sliding along the surfaces, a person exists inside these intersections. Earlier, in other terms and scales, Gaston Bachelard (1884–1962) also spoke of something similar, proposing reader of »The Poetics of Space« (1957) the idea that people exist not in rooms in their architectural sense but inside images with which these rooms are filled, and which set a certain »tonality« to our beings.

When applied to an artist’s studio as a space of creative production, these concepts are a way of contextualizing and understanding the process of art-making. In particular, the ideas which address public spaces, since a studio usually serves not only as a place for artistic production but also for public showings, discussions, tête-à-tête or collective gatherings. This also applies to the studio of Bernhard Heiliger, one of the most prominent artists of post-war Germany, who lived and worked in the East wing of what is today Kunsthaus Dahlem from 1949 until his death in 1995.

Based on the logic of the ideas and concepts indicated above, a simple atelier’s interior reconstruction is unsuitable for understanding Heiliger’s thought process. For not even the most accurate reconstruction of the »room« is able to bring the viewer closer to its authentic content at a distant moment in time and for a specific person. The best method might be to engage with the art pieces created here. Because, as Merab Mamardashvili (1930–1990) concluded, it is precisely the works of art and literature that capture the individual content of the common time and space of existence, the »special dimension of the conscious life« of their authors. So, to get closer to the understanding of Heiliger’s special »mode of existence« within a shared historical context, this exhibition focused on one particular geometrical form as a key element in the artist’s oeuvre and how it entered his formal canon.

While in the early years of his career, the artist exclusively worked in figurative manners, he then gradually moved towards a more bio-morphic and semi-abstract style in the late 1940s before finally turning to full abstraction and the composed arrangement of geometrical forms. This late, »technical« period of Bernhard Heiliger’s work is marked by the repetition of the circle as a key motif. In an interview with Eberhard Roters, Heinz Ohff and Wieland Schmied, when answering the question of how the circle came up in his works, Heiliger stated that »By mistake, actually. It was a dot on the sheet, which I then encircled.« (1981) Having accidentally found this shape, he remained committed to it for several decades. »Every being in itself seems round,« Karl Jaspers (1883–1969) once wrote. As if vainly trying to gain this independent, self-sufficient »being-in-itself« or, as critics said about the motive of Heiliger’s creativity, »to overcome space and time«, the artist moved the circle within his compositions, realizing it in various materials, narrowing it to a geometric plane or expanding it to a three-dimensional object.

Yevheniia Havrylenko

Guest curator at the Kunsthaus Dahlem,

funded by the Ernst von Siemens Art Foundation